The car did it? Accountability in the age of self-driving cars

Accountability is a sticky concept already, and one with several branches of law committed to unraveling it. If we get involved in a car accident today, it requires a great deal of effort to assign blame to one or more human parties.

Self-driving cars carry the promise of vastly simplifying our understanding of accountability, legally speaking. But it might take years or decades for the technology required for this vision to become widely available.

In the meantime, cities, states and countries are moving at their own pace in allowing the test of autonomous cars on public roads and declaring deadlines for new laws concerning their use — including accountability in the event of a roadway incident. Here’s what we know so far about the several ways this technology is expected to upend the idea of “accountability.”

Accidents and “Acts of God”

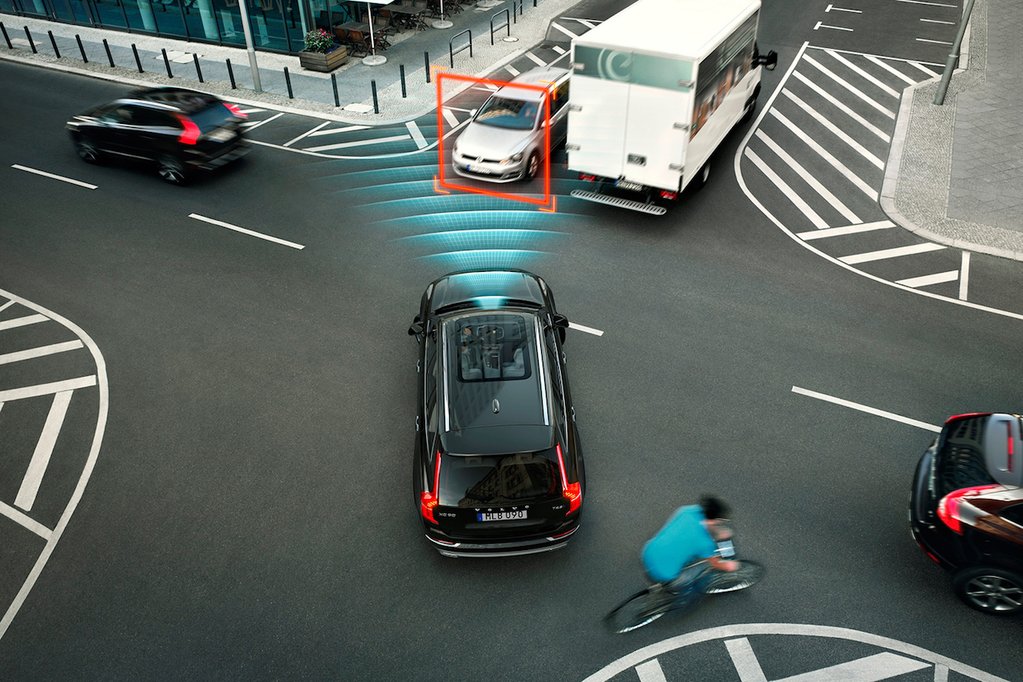

There will likely always, unfortunately, be the possibility of collisions out on our roadways — between automobiles or between automobiles and passersby. In March 2018, an autonomous Uber struck and killed a 49-year-old pedestrian in Tempe, Ariz. Was this an “act of god,” or a faulty line of code?

According to some accounts, the pedestrian “stepped out from the shadows” into the path of the car. By other accounts, the vehicle was requesting that its pilot take manual control. In either case, it was the first known instance of a driverless car killing somebody.

We live in a world where we can trace 94 percent of car crashes to user error. There’s little question that autonomous and even semi-autonomous cars are going to save a lot of lives, money and collateral damage. But consider how things might’ve played out instead.

Uber paused its testing program during the incident investigation, but has since resumed. All the company’s vehicles operate at a “level 4” for autonomy, indicating it shouldn’t require human intervention. It’s possible and even likely a court would have found Uber liable if there was evidence the vehicle had made an “error in judgment.” Instead, there was every indication the pedestrian had acted recklessly.

Back in 2015, the governor of Arizona issued an executive order to hasten the testing of autonomous cars on Arizona roads. Many other states have issued similar permissions and delivered deadlines to independent bodies and government commissions to draw up rules governing the use of driverless vehicles within city and state lines.

The result is likely to be a patchwork of laws for some time. At the federal level, the Trump administration is following the Obama administration’s lead with a “light touch” to regulation when it comes to driverless cars.

Children Using Self-driving Vehicles

Can minors use autonomous cars? Could a parent one day strap their child into a driverless car and send them off to Grandma’s house? What if that car causes, or is otherwise involved in, an accident?

We know there’s an inherent risk in using fast-moving automobiles of any kind. And in the case of a driverless car, all we’ve swapped out is human intuition with a computer’s. Why should the latter give us pause at this point, when many of us have made peace with sending our children unaccompanied on public buses or on airplanes?

We need to address several social, regulatory and technological barriers before children could or should be legally permitted to “operate” driverless cars:

- The vehicle would have to be certified “level 4” or likely “level 5” autonomous, indicating no need for human interaction in any circumstances.

- The vehicle would require some deep level of parental surveillance, including location tracking, remote override, communication systems and even onboard cameras.

- In the case of autonomous school buses, there would likely always be an “approved monitor,” with a license from a relevant governing body, who can more immediately communicate with dispatchers or intervene in an emergency.

When it comes to children and driverless cars, the strong social stigma against placing our children in the care of unknown persons, to say nothing of unknown technology, probably outweighs the practical and regulatory implications.

Drunk Driving and Self-driving Cars

It seems like a no-brainer: Cars that don’t need drivers probably don’t need sober drivers, either. The problem with this logic is we’re relatively far away from the level of autonomy required for our day-drinking fantasies to come true. We’re years away, according to IEEE, from full autonomy being either a common option (2024) or a mandatory feature (2044) in new cars.

In the meantime, we have to determine accountability in the context of “tiers” of automobile autonomy. It’s a problem that’s occupying the time of an independent panel, on behalf of the Australian government, as we speak, with the intention of furnishing guidelines by 2020. Specifically, they want to determine two things:

- How “autonomous” would a self-driving car have to be for an intoxicated person to be able to operate it successfully?

- Should an intoxicated person be penalized for operating such a vehicle, when the alternative would have been driving a conventional automobile?

The Australian National Transport Commission is offering the logic that drunk driving offenses should be brought only against people who operate a vehicle manually while intoxicated — not those who start up a driverless car. That assumes a fully autonomous car, of course.

For context, in the U.S., intoxicated passengers of an automobile can be charged with a DUI even if they weren’t driving the car. Until we get a major rewrite of our laws, it might be some time before we can pack our blackout-drunk friends into the back of a driverless Prius or Tesla to get them back home.

Loans and Leases

Some legal scholars maintain liability in any event involving a driverless car will be, in the future, less about vehicular misuse or negligence and more about “product liability.” We know companies like Uber and Lyft envision a future where they own and operate fleets of roaming cars for hire. It’s hard to imagine such a business model taking shape without Uber and Lyft bearing all or most of the liability — when they developed and deployed the technology and declared it safe for public use.

But who’s covered and who’s not, if one of us owns an autonomous car and loans it to somebody else?

This is hypothetical today and mostly unknown. Today, we don’t insure our vehicles so much as the people who drive them — and insurance companies always know who our designated vehicle operators are, because it’s on the paperwork. We don’t typically loan our cars to others because other parties aren’t covered.

The potential of fleets of cars for hire, and the ease with which we could share tomorrow’s driverless cars with friends and family, is a massive part of their appeal and promise. It would be a blow to that idyllic future if individual operators were the ones bearing the most substantial burden regarding liability.

It’s much more likely that near-future governments and the public will ask these technology companies for liability equal to their ambition, no matter who’s using their products, or where, and provided all parties were acting lawfully at the time.

And that brings us back to benchmarks like 2020 and 2024, when cities and states hope to have such laws ironed out for good. In the meantime, the burden of proof rests on the tech companies promising safety and convenience with no downside.